13 Dec Why Was Cecil Beaton Such A Bright Young Thing?

With knowing glances and cutthroat wit, the work of Cecil Beaton offers a glimpse into the glamorous world of 20th Century high society.

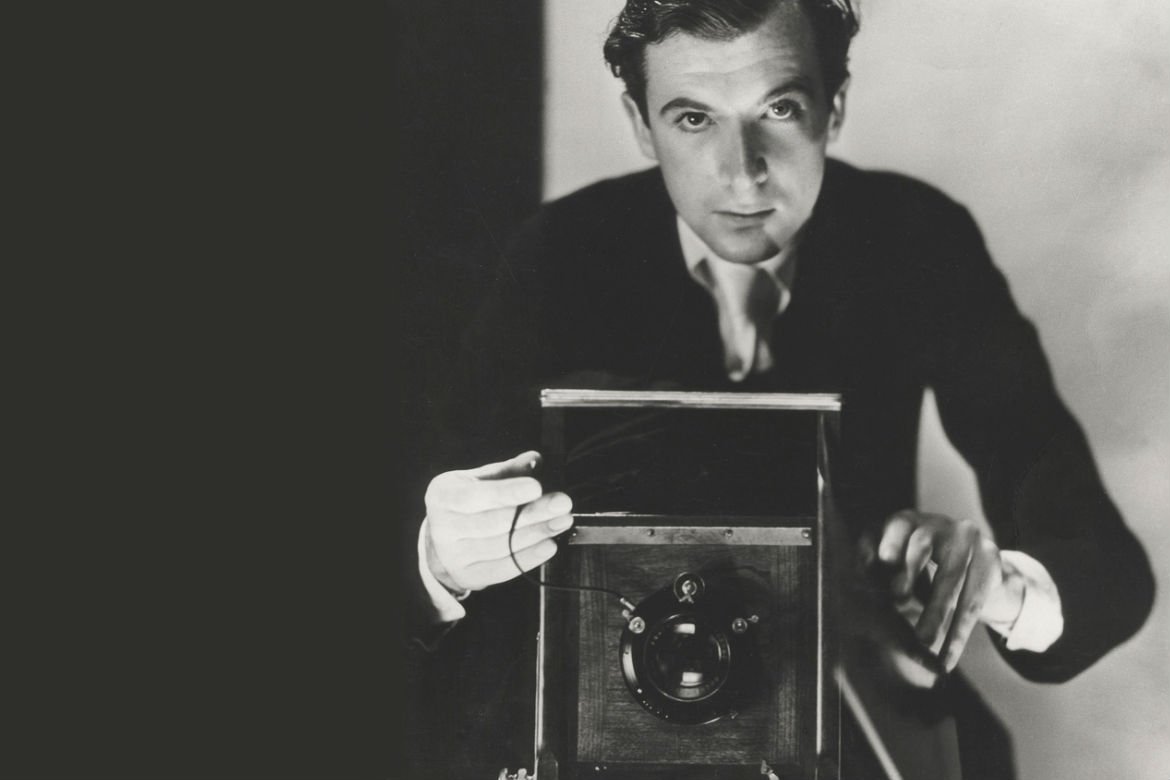

From debauched bohemians of 1920s London and the stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age, to the British monarchy and the devastating effects of the Blitz: armed with his trusty camera, Cecil Beaton flitted effortlessly through the most significant moments of the 20th Century. Although he was certainly less than perfect on a human level (by which I mean to say, he was a bitch), I have long been fascinated by Beaton and his work. Blending glamour, social commentary and a little flash of magic, his impact on the world of fashion photography cannot be underestimated.

Beaton was only 23 when his lifelong affair with Vogue began. Armed with just a few smatterings of experience and the Kodak 3A Folding Camera that he’d been using for over a decade, he made his first contribution to the magazine in 1924: a portrait of the distinguished academic George “Dadie” Rylands. By all accounts, Beaton was surprised that they deigned to published the slightly unfocused shot.

However, it was his portraits of The Bright Young Things that really put Beaton on the road to notoriety. Christened thus by the tabloids of the day, The Bright Young Things were a group of young aristocrats with nothing better to do than drink, party and experiment (in all the ways you might imagine). The press of the time stalked them with great enthusiasm, allowing eager readers to follow along with their hedonistic antics. Kind of like a pre-internet Made in Chelsea.

In both his personal and professional life, Beaton was always the outsider trying to get in. Being apart from what he was a part of provided him with a unique viewpoint from which he could pass insightful (often cynical) comment.

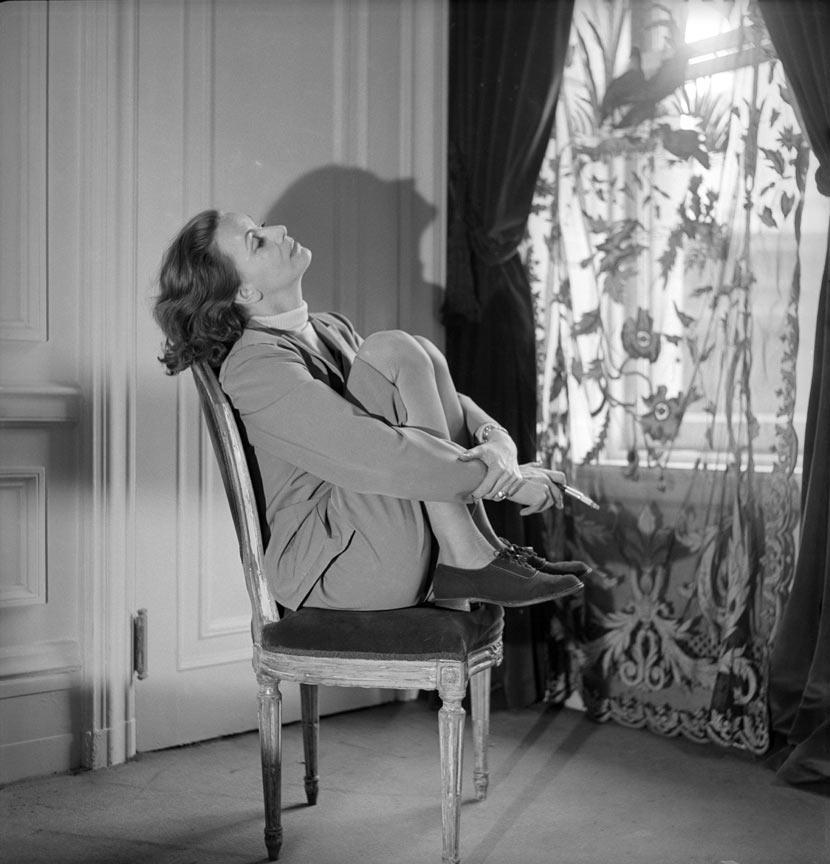

In 1928 Beaton moved to New York, where he landed a full-time position at Vogue. In this glittering world, moving in glamorous circles populated by his fellow aristocratic socialites, he thrived. At a party in Hollywood, Greta Garbo handed him a rose with the words: “a rose that lives and dies and never again returns.” This was the beginning of the great obsession of Beaton’s life — but more on that later.

His career was on the up when he created the first of his eight Vogue covers (below). However, it all came crashing down around him in 1938 when newspaper columnist Walter Winchell spotted a hand-scrawled anti-Semitic slur in the margin of one of Beaton’s illustration’s for Vogue. Beaton apologised and claimed it was a “silly joke”, but the damage was done.

It’s often hard to reconcile the beauty of Beaton’s work with his failings as a person. The question of whether we can love the art and not the artist — and whether we should — is difficult to answer. Aside from that nasty streak of anti-Semitism, Beaton’s inherent cynicism frequently grew into something ugly. In his private notes, he sketched his ‘friends’ with an acid pen. Katharine Hepburn was “a raddled, rash-ridden, freckled, burnt, mottled, bleached, and wizened piece of decaying matter.” Even Greta Garbo appeared “almost simian” at dinner one night, with “untidy hair and large, smudged red mouth.”

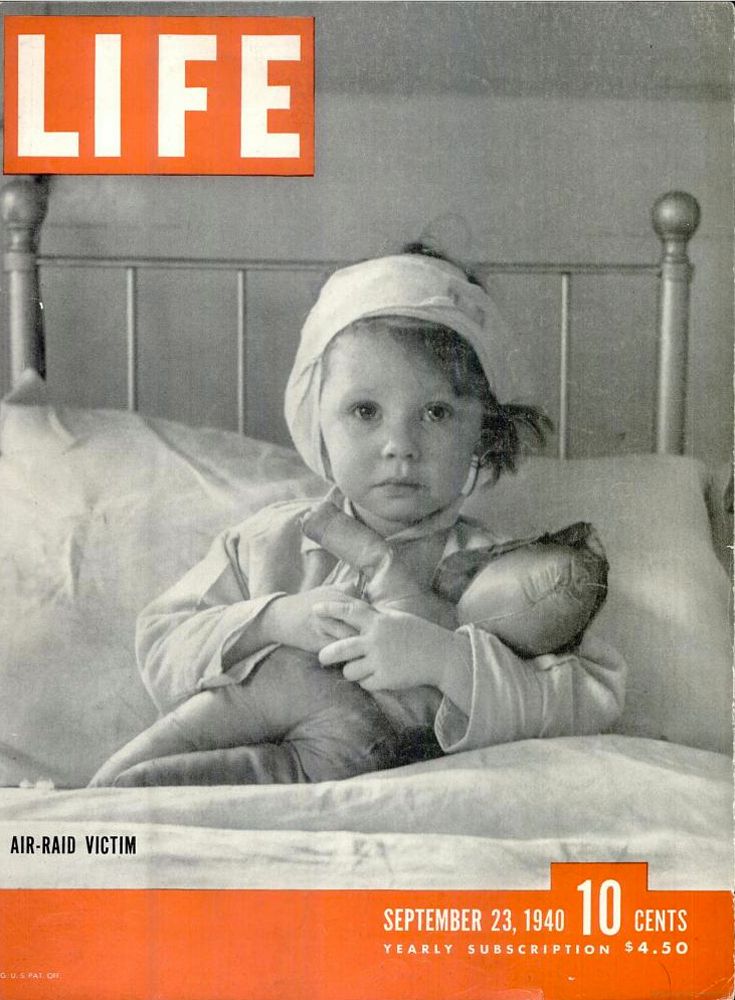

His reputation in tatters, Beaton returned to Britain. Despite his anti-Semitic remarks, some of the most lucrative years of his career were still to come — and in many ways that doesn’t feel particularly fair. His portraits of Queen Elizabeth II are now iconic, as is the below image of a three-year-old air raid victim. Taken at the height of World War II, it is said that this photo was instrumental in persuading the USA to join the war effort.

Around this time, Beaton also began designing costumes for the theatre, an interest which he would pursue for the rest of his life. He also took a series of photographs of the elusive Garbo, and Vogue published them all in 1946; despite the fact that the actress had only approved one photo for publication.

Garbo was not happy, but she got over it. Soon after, the pair began a love affair that would last for years.

She was not the only actress to play Beaton’s muse. His intimate portraits of Marilyn Monroe draw out the delicate, playful nature of a woman who was widely viewed as a vacuous sex symbol.

And of course, there was Audrey Hepburn (if you haven’t read why she should be everyone’s style icon, you may do so here). Beaton was a fan of Hepburn’s from the start of her career, writing that she “gives every indication of being the most interesting public embodiment of our new feminine ideal.” In 1964, he designed the costumes for My Fair Lady and photographed Hepburn in the starring role.

Even in his 60s, Beaton was still going strong. From Mick Jagger to Andy Warhol’s Factory, he continued his quest to capture on celluloid the feeling of belonging that had eluded him for so long. Unrivalled in his creativity and versatility, Beaton never lost his intuitive ability to unveil the true nature of his subjects; from rockstars and actresses, to the Queen of England. Even to the untrained eye, his work proves that a beautiful photograph is more than technical expertise and expensive cameras. It’s that tiny spark of magic that ignites between the model, the lens and the photographer.

Four days after his 76th birthday, Cecil Beaton died in his home in Wiltshire. To the world of fashion photography, he left a rich visual legacy. To Greta Garbo, he left a painting of a single rose.