06 Jan A Brief History of Pink

As told via iconic fashion moments.

In the history of fashion, no colour has been so fiercely debated as the colour pink. Encumbered with a symbolism that shifts across time and geography, a pink outfit will always attract analysis. When Hillary Clinton gave her first press conference as First Lady, her rose-hued sweater turned political commentators into fashion specialists.

“Mrs. Clinton’s dilemma is that women have no business uniform,” wrote fashion critic Robin Givhan in 1996. “They have no garb that allows them to slip in and out of a situation without fashion commentary that mixes in pop psychology.”

But it hasn’t always been this way. Pink hasn’t always been laden, trifle-like, with levels of meaning. The Ancient Greeks and Romans didn’t deem pink to be important at all — they didn’t even have a name for the colour. When did we get so obsessed?

In Western cultures, the shift came at the end of the 17th century, when a new dye was discovered in South America that would transform the wardrobes of the European bourgeoisie — particularly in France, where we find our first pink style icon.

Baroque and Roll

The OG pink populariser. Madame de Pompadour loved the hue so much that porcelain manufacturer Sèvres named one of its shades Rose Pompadour in her honour. At the court of Versailles, where she lived as the King’s mistress, the colour soon became a symbol of fashionable opulence. At that time, it had zero connotations of gender (it wouldn’t get its feminine association until the 19th century, when men increasingly turned to darker colours and left the fun colours to their wives).

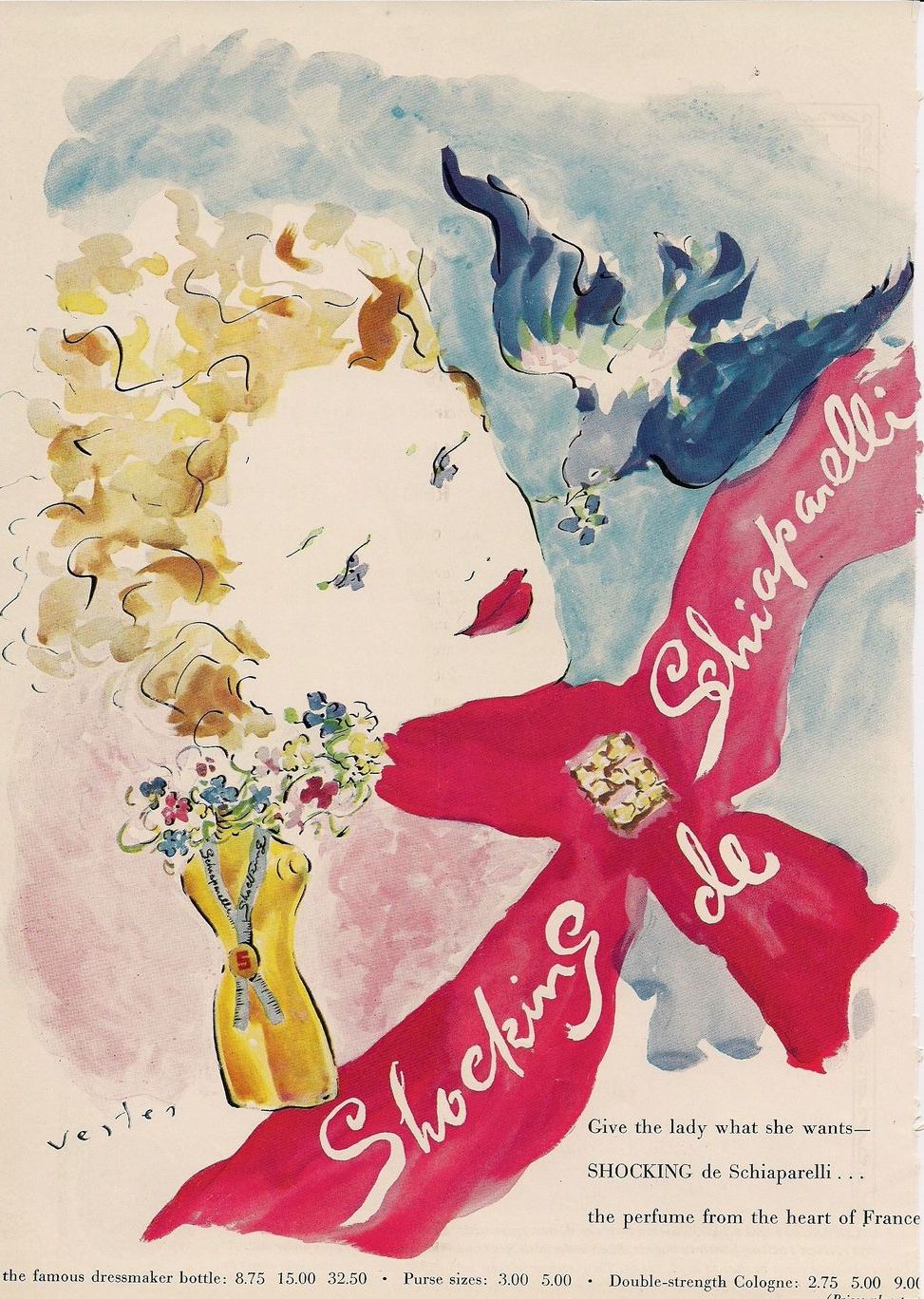

Shock and Awe

One of the 20th century’s most influential designers, Elsa Schiaparelli made use of new materials and technologies — such as non-fade chemical dyes — to utilise the full potential of pink. In 1931, she popularised a whole new shade: shocking pink. It was the perfect match for her avant-garde designs, and also inspired her signature perfume, Shocking.

Think Pink: The 1950s

Shampoos, toothpastes, the kitchen sink… as Kay Thompson sings in the iconic Funny Face number, commercialism was coloured pink in the 1950s; and that applied particularly to women’s products. For the first time, pink was directly equated with ‘femininity’ as women were pushed out of the workplaces that they had occupied during the War and back into the home.

That association was cemented thanks to two women in particular: First Lady Mamie Eisenhower, who supposedly loved pink so much that it even coloured the cotton balls in her bathroom; and movie star Jayne Mansfield, who covered the walls and ceilings of her bathroom with pink shag carpet.

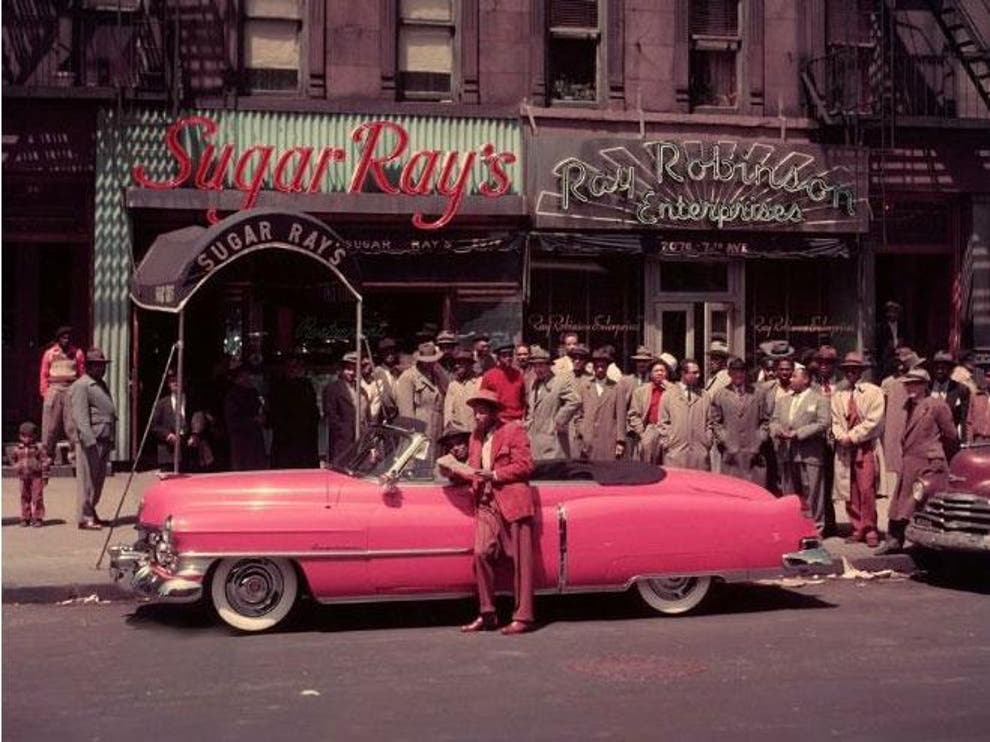

However, there are also some notable examples of men associating themselves with pink. Here’s looking at Elvis Presley, who stole basically his entire personality from black American culture and was therefore almost certainly ‘inspired’ by Sugar Ray Robinson in his choice of a pink Cadillac.

A Girl’s Best Friend

You know where I’m going with this. Mid-century cinema is full of iconic pink fashion moments, and the 1953 classic Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is one of them. The satin gown that Marilyn Monroe wore to sing Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend has gone down in herstory as a symbol of feminine confidence and sex appeal. Madonna famously parodied the scene over thirty years later in the music video for Material Girls.

It’s worth mentioning Grace Kelly’s coral ensemble in Alfred Hitchcock’s How to Catch a Thief, because it fulfils a similar role to Monroe’s Diamonds dress, albeit in a very different way. The story goes that Kelly requested that costume designer Edith Head create a ‘womanly’ look for the film’s final scene in order to show the character’s power and confidence in her own femininity (and I use the term ‘femininity’ in the context of the period; after all, the concept of ‘femininity’ is fluid, conditional to the place, time and individual in question).

Jackie O and the Pink Suit

The pink Chanel suit that Jackie Kennedy was wearing on the day of her husband’s assassination has come to represent a brutal turning point in recent US history. She famously refused to change before the swearing-in of President Johnson, or for the flight that took her husband’s back to Washington. The fabric was still visibly stained with his blood. It’s been viewed as a sign of her strength, but also as a symbol of the so-called ‘loss of innocence’ that followed the optimism of the Kennedy years.

LGBTQ+ RIGHTS IN THE ‘70s

The pink triangle has its roots in a dark past. An inverted version of the symbol first appeared as a way to identify gay men in Nazi concentration camps. For a long time, many survivors of this atrocity wouldn’t speak about their experiences; however, as more and more people began to speak and write about their experiences in the 1970s, the gay rights movement began to reclaim the pink triangle as a show of resistance and solidarity.

Grrrl Power

Before the Spice Girls, there were the riot grrrls. Led by feminist punks, the underground riot grrrl movement embraced pink and other ‘feminine’ details (think pigtails and hearts), reclaiming them as a symbol of female power in the face of double standards, rape culture and patriarchal values. “We are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak,” stated their manifesto.

MILLENIAL PINK AND BEYOND

Acne bags, rose gold iPhones, the cover of Drake’s Hotline Bling… we’ve come full circle. As it was at Versailles, pink is once again a delineator of style and luxury for all genders, every day — not just on Wednesdays (and if you thought I’d make it to the end of this without a Mean Girls reference, you clearly don’t me very well).